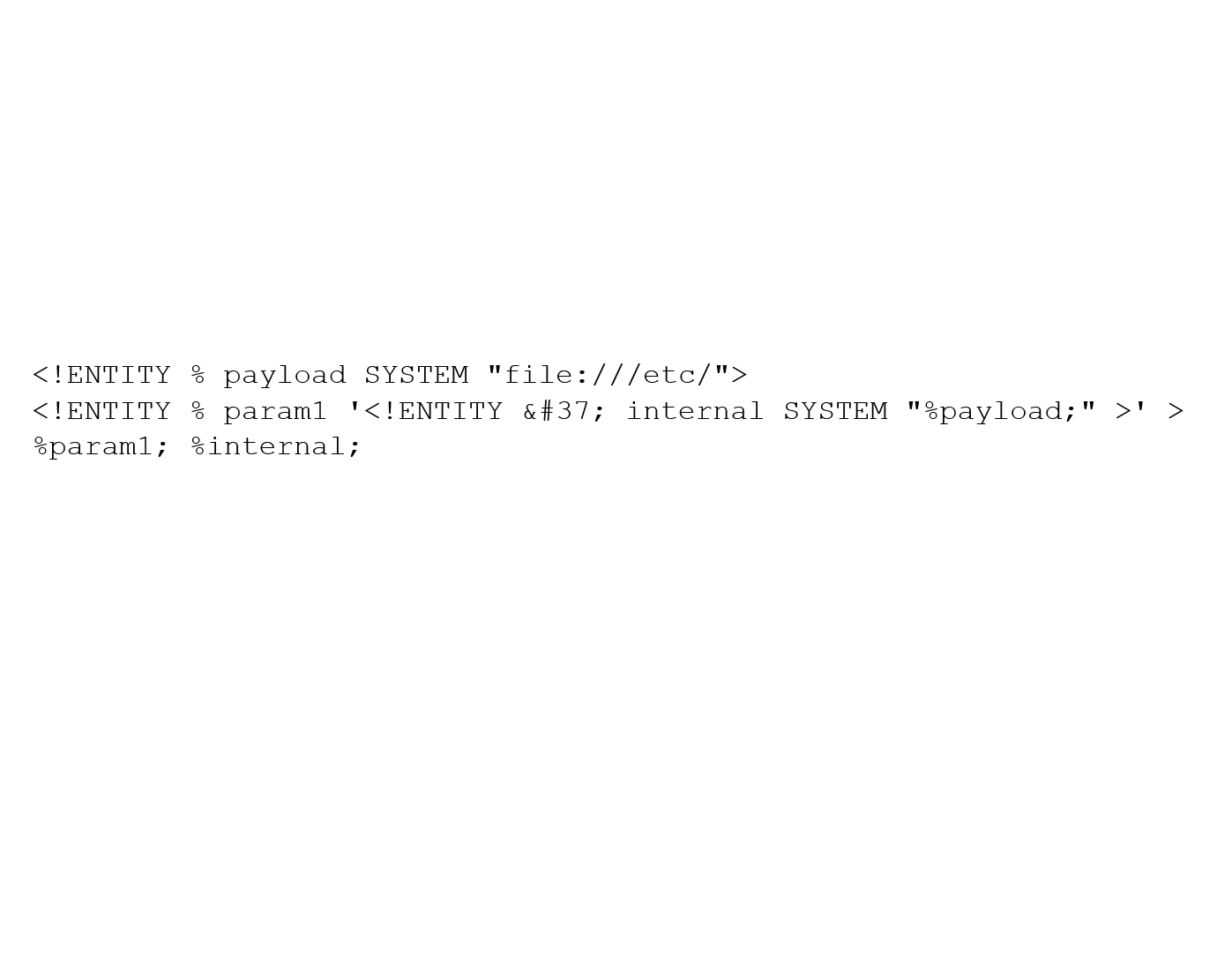

I was recently having a nose at the book O’Reilly Network Security Assesssment by Chris McNab. Early on the book describes the web app vulnerability of XML External Entity (XXE) parsing. In these attacks, malicious code is presented to a web app to cause it to return sensitive data. An example piece of XML (eXtensible Markup Laguage), which had previously been uploaded to the Google Public Data Explorer Utility, was given:

<!ENTITY % payload SYSTEM "file:///etc/">

<!ENTITY % param1 '<!ENTITY % internal SYSTEM "%payload;" >' >

%param1; %internal;

This piece of XML was found to return the file directory of the host system. The book glosses over how this attack works, and myself having only a passing knowledge of XML (i.e. that it’s a thing used to pass data on websites), decided to investigate a little further.

First up, what is XML? XML is a markup language that lets you represent data in a both machine and human readable format. For example, you could have:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<person>

<name>Bob</name>

<age>26</age>

</person></>

Various pieces of markup can be used to make ever more complex representations, but the above is the basic format. The excerpt provided in the book looks a little different. What’s it using here?

In the first line, we have:

<!ENTITY % payload SYSTEM "file:///etc/">

!ENTITY indicates that this is a Document Type Definition (DTD). DTD is used to define the structure and elements of an XML document. The !ENTITY tag indicates that we are creating an entity. In DTDs, entities are basically constants. They can often be used to present special characters which would otherwise be interpreted as part of formatting, such as & to represent &, or < to represent <. The entity consists of a name (“payload”), and an attribute SYSTEM “file:///etc/”.

There are two types of declaration for DTD entities: general, and parameter. A general entity may look like:

<!ENTITY address “22 Bobstreet Manchester”>

Any time &address; is used within a document, it will be replaced with the text “22 Bobstreet Manchester”.

A parameter entity may look like:

<!ENTITY % ContentType “CDATA”>

This would mean that any time %ContentType; appears within the DTD, it would be replaced with the text “CDATA”. CDATA is a keyword in XML used to indicate that a portion of text is character data, and so it can be useful to pass such terms around in the DTD.

Next up in our XML exploit, we have SYSTEM “file:///etc/”. This indicates that this is a private external DTD. External DTDs are used for creating DTDs which can be shared between multiple documents. There are two types of these: private and public. Private (indicated by SYSTEM) means that the DTD is intended to be used by a single author (or group of authors), and so may point to a local file. Public (indicated by PUBLIC) means that the DTD is to be widely shared, and may point to a web page. “file:///etc/” is the DTD location, or in this case, a file directory.

So, in the first line we have an entity called payload, containing a local file location, which can be called elsewhere within the DTD by referencing %payload;.

In the next line, we have:

<!ENTITY % param1 '<!ENTITY % internal SYSTEM "%payload;" >' >

What’s happening here is quite a bit of data passing. The first line of the system is being called through “%payload;”. As this is in quotation marks, the text “file:///etc/” has been passed in but not evaluated. The same has been done by using % to represent the percentage symbol. The result of this is that the entity param1 is being created and passed the following text:

<!ENTITY % internal SYSTEM "file:///etc/" >

This has essentially constructed a new %internal entity which can now be called.

In the final line, we see %param1; %internal;. Calling %param1 causes the above line of XML to be inserted in to the body, where it is then called by %internal. When the entity named internal grabs its attribute, it pulls text from the location that has been specified following the SYSTEM tag. In this case, it is the contents of file:///etc/, which is the contents of that filesystem (resulting in a list of all file names within this directory).

Why all these levels of abstraction? Why not just directly call the payload entity? In this situation, I can’t tell. I would say that it’s to avoid some piece of automatic detection, but the formatting of the resultant line is identical to the first. The final calls are also not being made in any particularly interesting locations (such as inserted in to other areas of the XML body), meaning that this was not the reason.

Any suggestions, please let me know!

Be First to Comment